Because of growing interest in self-report research on adolescent and adult romantic attachment, following the publication of "Romantic Love Conceptualized as an Attachment Process" (Hazan & Shaver, 1987), we receive an increasing number of requests each month for information, reprints, and measures. It has become impossible to respond to all of the requests individually, and rather than allow requests to stack up unanswered we have decided to provide a standard reply and a standard set of reprints and preprints.

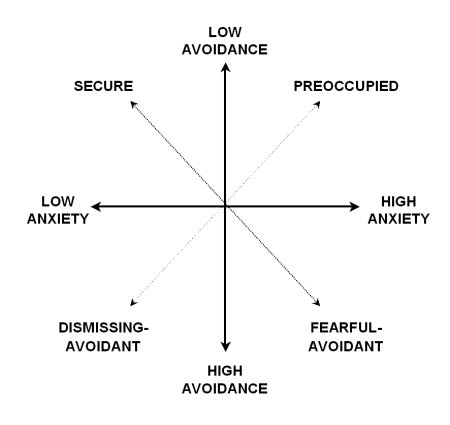

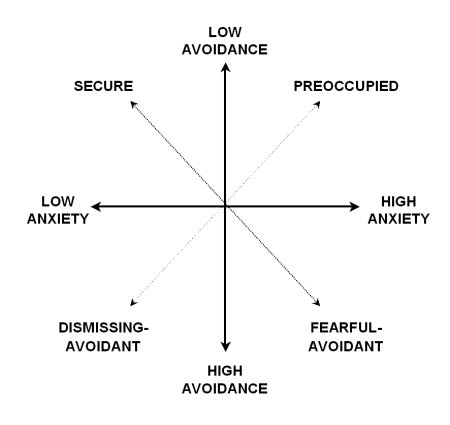

Many people still ask for the original Hazan/Shaver measure, and some sound as if they haven't read much of what has been published since 1987. That is a serious mistake! In the 1987 paper, Cindy Hazan and Phil Shaver were trying to assess in adults the kinds of "types" or "styles" identified by Mary Ainsworth in her studies of infant-mother attachment (see Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978), but focusing this time on romantic attachment. Hazan and Shaver wrote three type-descriptions based on imagining what adults who were like the three infant categories, but operating in the realm of romantic relationships, might be like. Subsequently, at least two important developments occurred: (1) Several authors broke the type-descriptions into agree-disagree items, factor-analyzed the items, and turned them into continuous scales. (2) Kim Bartholomew (1990; Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991) argued for a four-type (or four-style) conceptual scheme that included the Hazan/Shaver styles and added a second kind of avoidance (dismissing-avoidance, based on a similar category in the Adult Attachment Interview; see, e.g., Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). Underlying the four types or styles are two dimensions, Model of Self and Model of Other (or Partner). (For various reasons we prefer to call the two dimensions Anxiety and Avoidance--names closer to the manifest content of the items used to measure the dimensions. It remains to be seen whether they are best conceptualized in terms of cognitive models of self and other.) Bartholomew devised both interview and self-report measures of the four styles and the two dimensions that organize them conceptually (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The two-dimensional model of individual differences in adult attachment.

At the same time that these developments were occurring, other investigators continued to design their own self-report attachment measures, some based on attempts to capture the two dimensions that stand out in the analyses referred to above, others based on attempts to return to John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth's writings for more specific constructs such as compulsive self-reliance, ambivalent attachment, and compulsive caregiving. In 1998, Kelly Brennan, Catherine Clark, and Phil Shaver (1998) reported a large-sample factor-analytic study in which all known self-report measures were included in a single analysis. Brennan et al. (1998) found twelve specific-construct factors which, when factored, formed two more global factors--45-degree rotations of the familiar dimensions of Anxiety and Avoidance. Also, when the various authors' own subscales (totaling 60 in all) were factor analyzed, the Anxiety and Avoidance factors emerged clearly. At present, therefore, we recommend that researchers use the Brennan et al. (1998) 36-item measure (including an 18-item scale to measure each of the two major dimensions) for their principal analyses and reports of findings--or, if preferred, one of the other two-dimensional measures constructed by Chris Fraley or Jeff Simpson or Nancy Collins or Judy Feeney and Pat Noller or Dale Griffin and Kim Bartholomew (see references in Brennan et al., 1998). We also recommend that you conceptualize the patterns in dimensional terms, because Chris Fraley and Niels Waller (1998) have shown that there is no evidence for a true attachment typology; the conceptual types or styles are regions in a two-dimensional space. You lose precision whenever you use typological measures instead of the continuous scales.

Also, we would like to remind you that, as researchers, we should all continue to improve our measurement techniques. Although we believe that the multi-item scales, such as the ones developed by Brennan and her colleagues, are the best available at this time, we encourage attachment researchers to improve self-report measures of adult attachment still further. One step in this direction has been taken by Fraley, Waller, and Brennan (2000). For those who wish to know more about interview measures of attachment, most of which, with the exception of Bartholomew's peer/romantic interview, were not designed to measure romantic or peer attachment styles, see the review by Crowell, Fraley, and Shaver (1999) and the article by Shaver, Belsky, and Brennan (2000). For a discussion of similarities and differences between the Adult Attachment Interview, Bartholomew's peer/romantic interview, and self-report measures like the ones discussed here, see Bartholomew & Shaver (1998), and Shaver, Belsky, & Brennan (2000).

Measures and Papers Available at this Site

Measures

1.Hazan and Shaver (1987). This is the original self-report measure of adult romantic attachment, as slightly revised by Hazan and Shaver (1990). (Original psychometric information from 1988.

2.The Relationships Questionnaire (RQ). The RQ was developed by Bartholomew and published by Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991). This self-report instrument is designed to assess adult attachment within Bartholomew's (1990) four-category framework. Styles A and B correspond to the secure and fearful-avoidant attachment patterns, respectively. Styles C and D correspond to the preoccupied and dismissing-avoidant attachment patterns respectively. As shown by Brennan, Shaver, and Tobey (1991), Styles A, B, and C correspond respectively to Hazan and Shaver's (1987, 1990) Secure, Avoidant, and Anxious/Ambivalent styles. Bartholomew's measure adds the Adult Attachment Interview's (AAIs) dismissing-avoidant category and places the four categories into a two-dimensional model, something that neither AAI researchers nor Hazan and Shaver did initially. Shaver and Hazan (1993) have shown how the two dimensions fit with their initial ideas and with Roger Kobak's scoring system for the AAI (e.g., Kobak, Cole, Ferenz-Gillies, & Fleming, 1993). Brennan et al. (2000) show that the two dimensions are conceptually the same as the ones that Ainsworth et al. (1978, Figure 10, p. 102) derived from a discriminant function analysis of the coding scales used in Ainsworth's Strange Situation procedure for infants. In other words, Brennan et al. argue that the distinctions among attachment orientations have always been primarily a matter of scores on Anxiety and Avoidance. (The AAI, however, focuses primarily on coherence of discourse, not on Anxiety and Avoidance.)

3. Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR). The ECR is a 36-item self-report attachment easure developed by Brennan et al. (1998). The items were derived from a factor analysis of most of the existing self-report measures of adult romantic attachment. The measure can be used to create two subscales, Avoidance (or Discomfort with Closeness and Discomfort Depending on Others) and Anxiety (or Fear of Rejection and Abandonment). See the Brennan et al. chapter for more information on scoring. Brennan et al. derived four type or style categories from the two dimensions, and the categories predicted certain construct validity variables better than the RQ. But the sizes of the categories were quite different from the sizes one obtains with the RQ. (Differences between the category sizes obtained with different attachment measures are to be expected, given that the categories do not seem to be "real" except as regions in a two-dimensional space; see Fraley & Waller, 1998.)

4. Experiences in Close Relationships Revised (ECR-R). The ECR-R is a 36-item self-report attachment measure developed by Fraley, Waller, and Brennan (2000). The items were derived from an item response theory (IRT) analysis of most of the existing self-report measures of adult romantic attachment (see Brennan et al., 1998). Like the ECR, the ECR-R yields scores on two subscales, Avoidance (or Discomfort with Closeness and Discomfort with Depending on Others) and Anxiety (or Fear of Rejection and Abandonment). See Fraley, Waller, and Brennan for more information on scoring. A self-scoring version of the ECR-R is available on-line at www.yourPersonality.net.

Measurement Papers

The first three chapters are from the 1998 volume, Attachment Theory and Close elationships, edited by J. A. Simpson and W. S. Rholes and published Guilford Press. The chapters, in our opinion, are essential reading for anyone interested in learning more about the history of self-report measures of attachment, the controversies surrounding the use of types vs. dimensions, and the correspondence or non-correspondence between self-report and interview measures. The chapters are included here only for readers' information. Because the chapters are copyrighted by Guilford Press, they should not be reproduced without permission. The fourth paper reports empirical data on the links between the AAI and self-report measures of romantic attachment.

1. Brennan, Clark, & Shaver (1998). As mentioned briefly above, the Brennan et al. hapter contains one of the most recently developed multi-item measure of self-reported romantic attachment styles. The chapter also contains a brief history of self-report scales and a comprehensive overview of different scales.

2. Fraley & Waller (1998). The Fraley and Waller chapter reviews basic arguments, pro and con, for treating adult attachment patterns as types versus dimensions. After reporting extensive taxometric analyses on a large body of attachment data, the authors conclude that adult attachment is best measured and conceptualized in terms of dimensions, not as a categorical variable. Fraley and Waller also review several serious problems that may arise when categorical measures of attachment are used.

3.Bartholomew & Shaver (1998). Bartholomew and Shaver discuss the associations between self-report and interview measures of attachment. They point out important limitations of early research that failed to find an association between the two kinds of measures and discuss areas of overlap and difference between the two measurement techniques. This is a topic that will receive increasing attention in coming years.

4. Shaver, Belsky, & Brennan (2000). This article examines the relations between the AI, Bartholomew and Horowitz's self-report attachment measure, and the multi-item romantic attachment scales designed by Collins and Read (1990) in a data set collected by Belsky and colleagues. The research participants were 135 mothers of one-year-old infants who were tested in the Ainsworth Strange Situation. The quantitative coding scales from the AAI were all significantly related to self-report romantic attachment measures, even though the two typologies (from the AAI and from Bartholomew and Horowitz's measure) were not significantly related. The authors conclude, as did Bartholomew and Shaver (1998) and Fraley and Waller (1998), that attachment measures are more precise when analyzed in terms of dimensions rather than types, and that different measures of attachment are related at the level of underlying dimensions, despite differences in focus (child-parent vs. romantic/marital attachments), content (discourse and defensiveness vs. experiences in romantic relationships), and method variance (interview coding, social desirability biases, etc.).

If you are a novice in this research area, what is most important for you to know is that self-report measures of romantic attachment and the AAI were initially developed completely independently and for quite different purposes. (One asks about a person's feelings and behaviors in the context of romantic or other close relationships; the other is used to make inferences about the defenses associated with an adult's current state of mind regarding childhood relationships with parents. In principle, these might have been substantially associated, but in fact they seem to be only moderately related--at least as currently assessed. One kind of measure receives its construct validity mostly from studies of romantic relationships, the other from prediction of a person's child's behavior in Ainsworth's Strange Situation. Correlations of the two kinds of measures with other variables are likely to differ, although a few studies have found the AAI to be related to marital relationship quality and a few have found self-report romantic attachment measures to be related to parenting (e.g., Rholes, Simpson, & Blakey, 1996; Rholes et al., 1997.)

Summary

In summary, we place the greatest weight on results deriving from multi-item dimensional measures because they have demonstrated the greatest precision and validity (Brennan et al., 1998; Fraley & Waller, 1998). We encourage researchers interested in romantic and other close peer relationships to continue to explore the old measures in order to determine what their advantages and limitations may be, but not to base their primary analyses on these measures. We also encourage researchers to continue to concern themselves with measurement issues in this domain. Although we believe that substantial progress has been made in measuring adult romantic attachment and dealing with the theoretical issues involved, there are many gaps waiting to be filled and improvements waiting to be made.

Please see Crowell, Fraley, and Shaver (1999) for a more complete summary of current measurement issues in the field of adult attachment research and Fraley and Shaver (2000) for an overview of the concept of adult attachment used by members of Fraley and Shaver's laboratories.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147-178.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226-244.

Bartholomew, K., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Measures of attachment: Do they converge? In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 25-45). New York: Guilford Press.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46-76). New York: Guilford Press.

Brennan, K. A., Shaver, P. R., & Tobey, A. E. (1991). Attachment styles, gender, and parental problem drinking. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 8, 451-466.

Crowell, J. A., Fraley, R. C., & Shaver, P. R. (1999). Measures of individual differences in adolescent and adult attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 434-465). New York: Guilford.

Crowell, J. A., & Treboux, D. (1995). A review of adult attachment measures: Implications for theory and research. Social Development, 4, 294-327.

Fraley, R. C. & Waller, N. G. (1998). Adult attachment patterns: A test of the typological model. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 77-114). New York: Guilford Press.

Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item-response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psycology, 78, 350-365.

Hazan, C. & Shaver, P. R. (1990). Love and work: An attachment-theoretical perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59, 270-280.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524.

Kobak, R., Cole, H., Ferenz-Gillies, R., & Fleming, W. (1993). Attachment and emotional regulation during mother-teen problem solving: A control theory analysis. Child Development, 64, 231-245.

Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Growing points of attachment theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50 (1-2, Serial No. 209), 66-104.

Shaver, P. R., Belsky, J., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). Comparing measures of adult attachment: An examination of interview and self-report methods. Personal Relationships, 7, 25-43.

Shaver, P. R., & Hazan, C. (1993). Adult romantic attachment: Theory and evidence. In D. Perlman & W. Jones (Eds.), Advances in personal relationships (Vol. 4, pp. 29-70). London, England: Kingsley.